{This is our last post in 2025! We at the Calgary Gay History Project wish you a warm and festive holiday season – Kevin}

In the history of Calgary’s queer community, few figures loom as large—yet remain as quietly influential—as Doug Young. Born in 1950 near Taber, Alberta, and raised in both Taber and Medicine Hat, Young’s life was marked by a deep commitment to social justice and community building that helped shape the early gay rights movement in Calgary.

Young’s academic journey took him from Medicine Hat College to the University of Calgary, preparing him for a lifetime of advocacy and community service. Before his activism fully took hold, he worked with the Alberta Service Corps and Canada Customs—experiences that undoubtedly broadened his perspective on community needs.

But it was in the late 1970s and 1980s that Doug Young became one of Calgary’s most active voices for gay rights. At a time when queer communities were often hidden and marginalized, Young stepped forward into leadership roles that were both challenging and essential. He served as President of Gay Information and Resources Calgary (GIRC) from 1977 to 1979, and continued on its board through 1981. Under his stewardship, GIRC became a vital resource—offering support, outreach, peer counselling, and serving as one of the few community touchpoints for queer people in the city.

Young didn’t limit his work to one organization. He was actively involved with the Alberta Lesbian and Gay Rights Association, AIDS Calgary, Gay and Lesbian Legal Advocates Calgary (GALLAC), the Right to Privacy Committee, and the Gay and Lesbian Community Police Liaison Committee—a network of groups focused on legal rights, health advocacy, safety, and community relations. This breadth of engagement speaks to both the urgency of the issues at the time and Young’s own drive to see real, sustained progress.

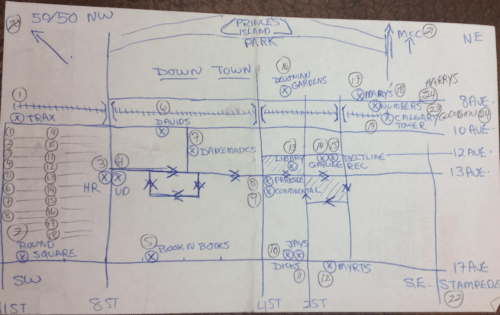

Young was an active spokesperson for the gay community and notably contributed to queer history through his extensive records. His personal papers were sorted and saved by Young’s friend John Cooper. They are now housed in the Glenbow Archives, which includes a remarkable hand-drawn map of gay spaces in the Beltline from the mid-1980s.

Perhaps most poignantly, Young’s leadership bridged the early gay rights era with the inevitable rise of the HIV/AIDS crisis. Community groups like AIDS Calgary grew out of activist networks in which Young was involved, helping mobilize volunteers, advocate, educate, and provide basic support during a time when fear and stigma often overshadowed empathy and action.

Doug Young passed away on April 15, 1994, from AIDS-related complications, a loss felt deeply across the community he helped nurture. While he did not live to see many of the legal protections and cultural shifts that came later, his efforts laid the necessary groundwork for Calgary’s queer organizations, public awareness efforts, and ongoing fights for equality.

At this dark time of year, I like to light candles to call back the light. I also light candles to remember those we’ve lost. Young would have been 75 in 2025 if he had lived, and I’m positive many other organizations would have benefited from his activism. The contributions of individuals like Doug Young are vital reminders of how far the community has come and how central grassroots leadership can make all the difference.

{KA}