{The first post from volunteer researcher Levin Ifko! Enjoy – Kevin}

Today I’m going to share some information about a column I found while looking through the online Calgary Herald archives via the Calgary Public Library. This archive has been useful in my attempt to better understand the way trans people may have been perceived by Calgarians, or perhaps more accurately, how trans people may have been presented to the Calgary Herald’s readership.

There have been quite a few findings here (many of which I’m looking forward to sharing with you shortly!). However, I wanted to begin my writing for the Calgary Gay History Project by sharing something near and dear to my heart and to my lived experience: figuring things out as a trans young person.

Described as a place where “young readers’ questions on human relations and sex are answered,” the “Youth Clinic” was a write-in advice column by Canadian psychiatrists Dr. Saul Levine and Dr. Kathleen Wilcox. Although initiated by the Toronto Star, the “Youth Clinic” grew to be syndicated nationwide. By late 1983, the Calgary Herald had picked it up, encouraging local readers to mail in their own questions to the Herald’s P.O. Box.

Between 1983 and when the Calgary Herald stopped syndicating the column in 1991, I found three separate queries from young people who wrote in to discuss questions relating to their gender. Although it isn’t quite clear where in the country these young readers are writing from, I believe and hope that these questions were seen by young people in Calgary who were having similar feelings.

The first question of this nature was published in 1984, with the youth writing

“Dear Dr. Levine: I am writing you this letter in hopes that I can better understand myself. You see, I am a bisexual male. No, that is not my problem. I’ve come to accept my bisexuality. Here’s where I need your help: I go by the name Sarah and have the uncontrollable desire to dress as a girl…”

The youth goes on to ask: “Why do I have this desire to be a woman?”; then inquires about accessing literature on the subject, and laments about how difficult the process may be to get the care they desire. I felt a pang of familiarity reading this question, which still feels tender when thinking about the road ahead as a young queer and trans person.

Another interesting note here is that the youth illustrates a common problem with accessing gender affirming care at the time: having to prove one’s same-sex attraction. This meant that gender affirming care would be given to trans people based on the belief that they were going to be exclusively heterosexual post-transition. As our young reader points out, “I’m bisexual. From what I understand I wouldn’t pass the program anyway.”

In 1985, another young person wrote:

“My problem is that I am a female in a male body. I have known since I was 5 years old. I am now 19. It is not an easy subject to discuss because most people have no idea how I feel. Sometimes I dress in women’s clothing and it feels so right. When I take them off, I become depressed and feel cheated and cry. I want to be a woman so badly.”

They go on to write, “I read any material available about transsexuals and sex-change operations, but such articles are usually vague or outdated.” This stuck with me, as access to information that is updated and relevant remains a common issue for trans young people to this day. Thankfully, since I came out in 2015, there has been incredible work done in this city to expand access. However, many times our best bet is still – of course – networks of support and understanding between other trans people.

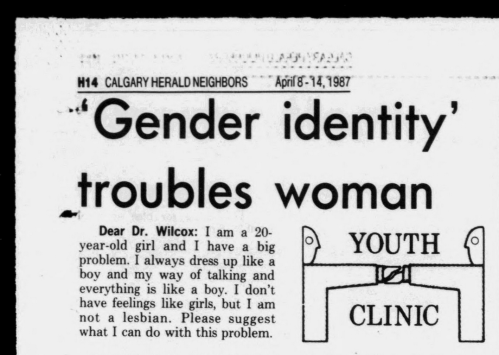

This last article excited me, as it’s not every day in the archive that you stumble upon discussions from youth who may be exploring transmasculinity. In 1987, this young person wrote:

“I always dress up like a boy and my way of talking and everything is like a boy. I don’t have feelings like girls, but I am not a lesbian. Please suggest what I can do with this problem.”

As for the answers to these youths’ questions?

Of course, the psychiatrists’ responses use terminology that differs from how many people view gender today, often referring to “transsexualism” as a “psychological-medical condition.” Yet I found that Dr. Levine and Dr. Wilcox did a pretty decent job of navigating some of these queries. Usually, they would explain the concept of “transexualism,” address some of the challenges and hardships these youth brought up, and using their expertise, encourage readers to further explore these feelings with gender specialists in their area, at one point acknowledging that “the definitions do not do justice to the complexity of these labels, nor the difficulties that those who are so depicted inevitably encounter.”

One response from Dr. Levine sounds eerily as if it came from today, when he writes “I am sure that as a result of this answer, I am going to get a barrage of letters for encouraging this person to get a sex-change operation, and by so doing, leading other young people down the path of iniquity.” But Dr. Levine goes on to encourage further exploration before a “definitive recommendation and plan of action are instituted.”

Really, the most exciting finding here is the truth. Young people, in this city and across the country, have always explored and questioned their gender identity. Youth have knowledge about their own gender and sexualities, and they can know and ask for what they want. As these records from the Calgary Herald show us, queer and trans youth have always been here.

{LI}